Turbulence in the care pathway

Those who work to improve society’s systems of care – think healthcare, aged care, disability care, social services and others – already know that many of the biggest challenges happen not only within each system, but also at their boundaries, where they intersect with each other.

As people move between systems, they experience turbulence, like an aeroplane crossing a patch of chaotic air. And like air turbulence, the bumpiness can vary in intensity. Sometimes, it’s barely noticeable at all. Sometimes, it’s frustrating, distressing. Occasionally, it can be consequentially harmful.

Care system turbulence will be familiar to many of us. It looks like this:

- Having to retell complex and painful stories again and again, with the risk of accidental omission or inaccuracy

- A missing, critical piece of a person’s health or social history at a point of care

- Multiple plans – treatment plans, care plans, wellbeing plans, recovery plans – creating an impossible-though-well-meaning tangle of a patient pathway

- A parent going through a neurodevelopment diagnosis journey for their toddler having to interact with a dozen different clinical, social and administrative providers, all disconnected from each other

- An A&E nurse treating a very ill patient with delirium, trying to raise pharmacists and GPs late in the evening to get a potentially life-saving patient history

- Data from a virtual care monitoring device not being able to be ingested into a digital health record, making it inaccessible to a range of providers

The Five Frictions and the care super-record

The reasons for this turbulence are well-known by policy-makers and front-line clinicians alike. While the boundaries of care systems are porous to people, they are often impermeable to data.

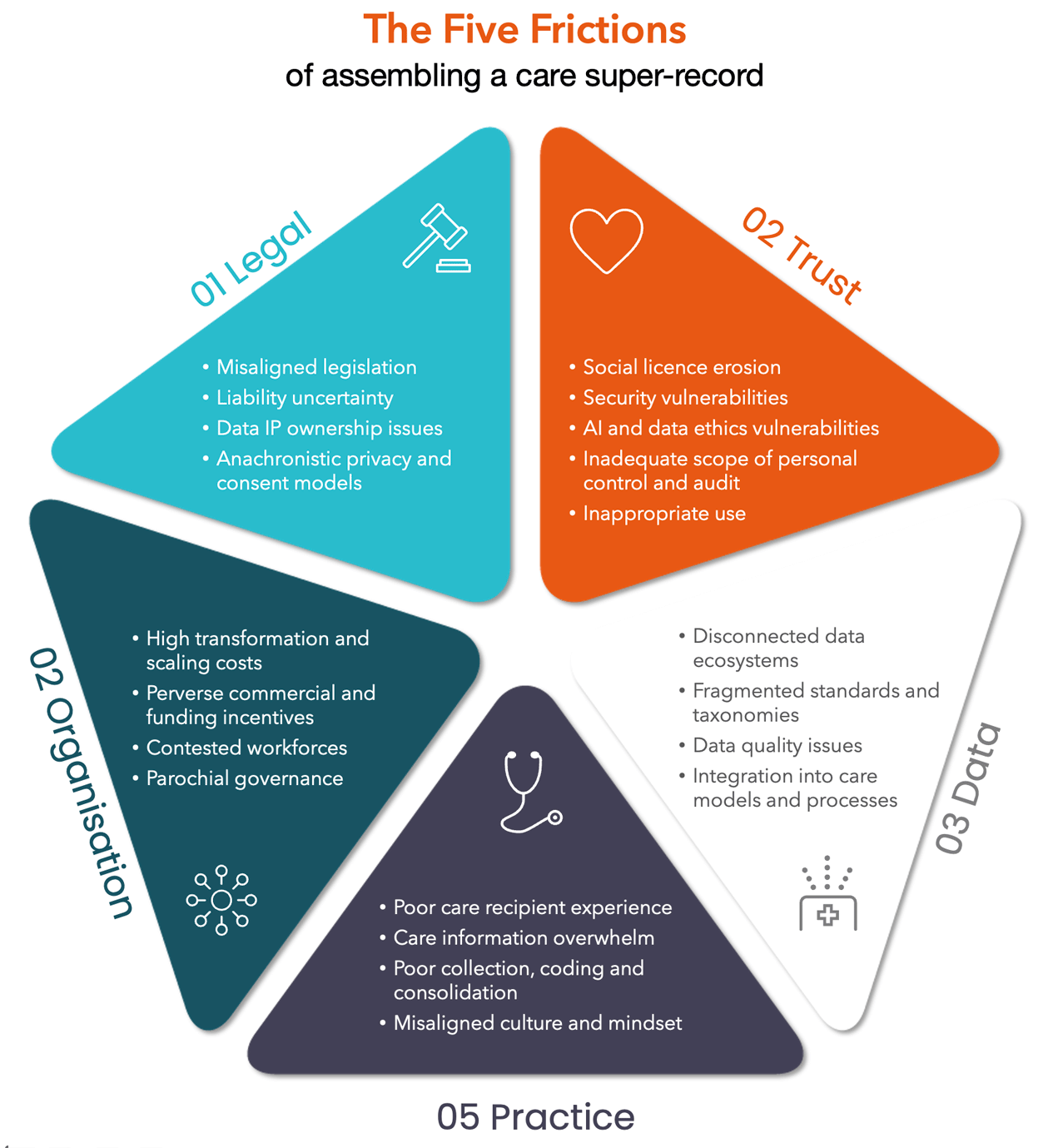

At ThinkPlace, we refer to them as the Five Frictions of assembling a care super-record – one that crosses the boundaries of multiple systems to record something approaching a complete picture of the care recipient:

There has been a herculean effort across OECD governments to incentivise or mandate care and clinical software interoperability, standardise coding systems, introduce digital patient records and care case management interoperability, join up care pathways, build collaborative cultures and blast away legislation that inhibits useful data sharing. COVID accelerated this in ways previously unimaginable by health authorities and providers alike.

Despite this, the care ecosystem remains fragmented and the challenge remains ponderous. The notion of a true care super-record remains far away.

Instead, we have the ‘Many-You’s’ problem. There’s Actual You – a complete person with a health, social, economic, geographic, genomic and community history and status. And then, there’s GP You, Hospital You, Social Support You, Bank You, Insurance You, Employer You, Psychology You, Podiatrist You – with each of these you’s cut down and often inconsistent versions of Actual You, assembled from the subset of data that’s managed to cross the boundary into each of these settings.

This is not all bad of course. For example, there’s no legitimate reason for your bank needs to know your mental health history, or your local council needs to know your medications list. And in fact, you may choose to assert controls over who can and cannot see your information up to the limits set by legislation.

But it is bad when the data needed to enhance your care isn’t mobilised at the point of care, simply because the pores of our care systems suddenly slam shut when information is trying to pass through them. Addressing the Five Frictions has been important enough to drive large investment agendas in the public sector at every tier of government.

But simply getting the clinical portion of the care record done has proven to be very difficult, due to the Five Frictions. The care super-record is a new level of challenge.

The AI multiplier

As we start introducing AI into the mix, the need to save this challenge gets even more urgent.

While AI that relies on very localised data input – say, that detects early sepsis risk – may not need a full patient history, grander models certainly will, and what they use to predict diagnoses, treatments and prognoses may be quite different from how these are determined today.

In an AI-rich world, the Five Frictions become at best a reduction in the effectiveness of care AI, and at worst, a source of error or a point of exclusion for those whose data is thinly spread around the care super-system. Overcoming the Five Frictions, on the other hand, creates a new opportunity for unified care that treats the real, complete human in a way that has never been possible before.

And that’s an exciting thought.